First, a disclaimer: I am no lawyer. Like most people, I am not versed in the arcana and intricacies of legal and constitutional matters. Even so, like many, I know legal abracadabra and bullshit when I see it.

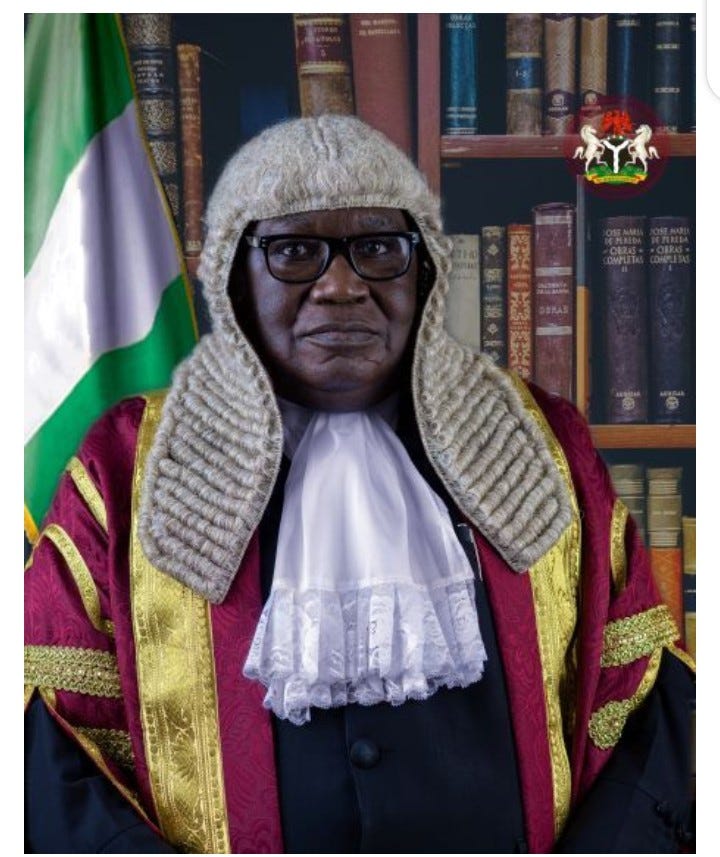

On September 6, 2023, I beheld Justice Haruna Tsammani and his cohort of four justices as they served up a dollop of deodorized shit.

Tsammani & Co, members of the presidential election petitions tribunal, delivered their verdict on three petitions filed against Bola Ahmed Tinubu, his party, the All-Progressives Congress (APC), and the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC).

In sum, the petitioners beseeched the court to make three key findings. One, that Tinubu was not qualified to be a candidate. The prayer rested on a few planks. There was evidence, for one, that he has a second citizenship in Guinea.

He was also mired in legal trouble in the US related to drug trafficking, an issue he resolved by agreeing to forfeit $460,000. Also, there are discrepancies and questions galore around Tinubu’s academic credentials.

Finally, Tinubu’s vice presidential pick, Kashim Shettima, was at some point a “double” candidate, listed as running for a senatorial seat.

The issue of qualification apart, the petitioners contended that Tinubu failed to meet certain benchmarks of the electoral law.

INEC erred, then, in declaring Tinubu the winner of the February 25, 2023 presidential election. Worse, they accused the electoral body of egregious violations of the laws spelling out the conduct of elections, including modes of transmitting results.

If you followed the proceedings, you were likely curious that Tinubu and INEC would team up to oppose live airing of the hearings. Why, if both parties had nothing to hide, would they make this strange entreaty? And why did Tsammani and his colleagues accede to this request, limiting Nigerians’ access to the legal jostle in real time?

In retrospect, with the benefit of the justices’ vapid verdict, their shameless abandonment of their hallowed bench to assume the mantle of defense lawyers, it is hard not to conclude that the fix was in from the outset.

To arrive at their “considered judgment”—an omnibus dismissal of all claims in all three petitions—the justices needed to resort to a slow-walked marathon riddled with technical mumbo jumbo. It was a masterclass in judicial obfuscation.

The delivery of the judgment lasted more than twelve hours—time that nobody, least of all those who endured the whole uninspiring show in its entirety, would ever get back.

Perhaps Tsammani and company created a Nigerian, African, or even world record as the longest time reading a judgment. It was as if the five justices believed that longevity would confer the grace of erudition on their performance.

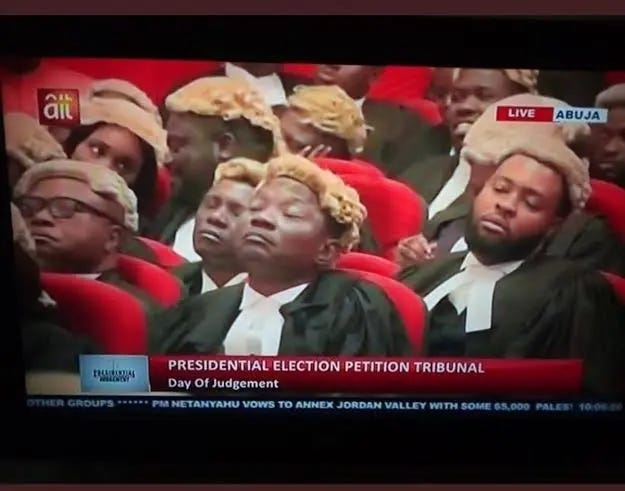

If so, they are profoundly misconceived. The most telling response to their long-windedness was a visual one, beamed to the world by TV cameras.

It was in those viral images of lawyers, reporters, politicians, and spectators sleeping away as the justices shambled through their tome. Far from being erudite, the voluminous verdict was a tawdry document, a monument to judicial spinelessness.

I bet that most Nigerians expected exactly the judgment that the tribunal vomited on September 6, not because it aligned with the legal principles, but precisely because it wasn’t. Those who rig elections in Nigeria know that the more manifest their impunity, the higher the odds of finding judges to croon that the cheated petitioners had not met the burden of proving their case.

In this respect, Tsammani & Co have earned their spots in the hall of infamy.

The justices fooled no one. Nigerians saw the electoral show of shame that was the presidential polls on February 25. They saw how INEC broke each pledge about conducting an impeccable election. They witnessed the snatching or stuffing of ballot boxes, the sabotage of the electronic infrastructure for the election, the failure to electronically transmit poll results.

Tsammani and his fellow traffickers in judicial perfidy were not perturbed in the least. They never sanctioned INEC for dragging its feet when petitioners asked for electoral documents that was their clients’ entitlement. Instead, these judges were content to don the garb of defense lawyers.

They made up judicial “facts” as it suited them. They advanced arguments that even INEC’s lawyers dared not make. INEC was required to upload results electronically.

The justices not only excused the electoral body’s widespread defiance of this requirement. They invented the spurious argument that INEC circumvented the law because the electronic mandate was susceptible to hacking.

What a low moment for the judiciary! Tsammani and his fellows expunged from the record ten out of thirteen witnesses called by the Labor Party and fifteen out of the PDP’s twenty-seven witnesses. They gutted all documents tied to these erased witnesses, all so that the tribunal could declaim that the petitioners’ case was bereft of merit.

Tsammani and his judicial bedfellows were in a haste to dismiss and discountenance witnesses merely because they happen to be registered members of some party that invited them to testify. It’s all akin to tying a man’s hands and legs, and then accusing him of inability to kick a ball past a goalie.

I repeat—I am no lawyer. I suspect some brilliant legal minds are already scrutinizing Tsammani & Co’s judgment, underlining its shaky legal principles, its inconsistencies, and shoddy innovations.

Layman that I am, I can—like millions of Nigerians—intuit a sham. Tinubu’s so-called election was a sham. The Tsammani-led tribunal’s effort to lend legitimacy to that sham struck me as pathetic and wholly unconvincing.

By Okey Ndibe

Okey Ndibe wrote via Offside Musings